Testing and the Lure of False Positives

Testing and the Lure of False Positives

"This class has made me realize how much meaningless memorization I go through." —Jackie J.

"I never even need to look at the book while studying for a test. If I have paid attention in class every day and if I take good notes, then all I need to do before a test is study my notes so all those ideas are fresh in my brain." —Liz L., student

Assessing what we know and don't know is an essential ingredient in any learning process. It both celebrates what we have mastered and identifies what we still need to learn. Above all, assessments must provide students with feedback and a remediation process to learn from their mistakes.

Regurgitation vs. Merit Badges

Regurgitation vs. Merit Badges

It is the second week of school and we are continuing our discussion of the philosophy and structure of this class. I give them a minute to settle in, get comfortable. The effect of the light in the room, a combination of daylight coming through the large bank of south-facing windows and the table lamps around the room, makes for a peaceful atmosphere. The orange Persian rug, dilapidated as it is, adds warmth to the room, andthe trees in the courtyard outside the windows are in full fall color. I love teaching in this room; it lends itself to comfortable conversations.

Today, I want to challenge them to rethink the purpose of testing.

“How many of you have memorized something for school, especially in the last day or two before a test, regurgitated it on the test, and then forgotten it within, say, a week or two?”

Every hand goes up, just as it has every time I’ve asked the question.

“Do you think this a common occurrence?” I ask.

There is a chorus of responses telling me that it happens all the time, that this is what school is.

Then I ask, “How many of you think this cycle of cramming, testing and forgetting is useful or meaningful in your life?”

Not one hand goes up. Not one hand has ever gone up in all the years I’ve asked this question.

“Okay, let’s say you have crammed for a test and done well on it. Say you aced it. Does it mean you have learned the material?”

David speaks up. “Absolutely not.” David is tall and very thin. As will become evident over time, he drives himself hard as a student. “Sometimes I learn the content, sometimes I don’t, but either way, I always do well on tests.”

With a little prompting, a flood of conversation wells up. Every student has stories to tell of what it feels like to cram for a test and how futile the process is. They bemoan the lack of learning required, and complain that teachers don’t really care whether they are learning.

It’s time for me to weigh in. “Well, I happen to think that most teachers really do care whether you are learning. In fact, they care a great deal. The teachers I know and respect are constantly looking for ways to help their students learn more. So something about this is really not adding up.

“It sounds like we all agree that cramming, regurgitating and forgetting is a pretty meaningless thing to do. It’s part of what I call “doing school”, going through the motions, doing a lot of pointless activity for the sake of getting grades. We’re going to be spending a lot of time in the next few days talking about doing school, because I believe we can do much better than that.

“In fact, I would like for us to create a place where genuine, meaningful learning is the real purpose for our being here. When I say ‘genuine learning,’ I don’t just mean learning about Physics. I believe it is even more important that you learn about yourself: knowing how you learn, how you work with others, how aware you can become of your motivation to learn or to keep doing school, how well you steer your own learning process. I want every one of you become active participants in the process. If we’re going to do that, we have to rethink everything we do so that it will actually serve the purpose of learning, including how and why we take tests.

“The good news is, there is a totally different way to think about tests than cramming and forgetting,” I continue. “Here’s an analogy that helps explain it. Oddly enough, it comes from the Boy Scouts, who have these things called merit badges. If you learn enough about a given topic, you are rewarded with a badge that says you have mastered the topic. It turns out there are dozens of different badges for things like orienteering, first aid, archery and so on. Back when I was a kid (yes, I was a Boy Scout), they had a badge for Morse Code, and another one for Knot Tying.” A couple of the guys roll their eyes; they are very comfortable on the street, and this Boy Scout stuff about archery and Morse Code probably strikes them as childish.

“So here’s how it works. Let’s say you want to get the badge for Knot Tying. You are given a list of fifteen knots you need to master and some instructions on how to tie them. On your own time, you practice until you think you can do all of them. Then you go to the Scoutmaster, and show him what you can do.

“Now, let’s say you can only tie eleven knots correctly. You thought you could do all of them, but you just can’t remember how to do those last four. You don’t get a sixty-six percent or a C minus for your efforts. Instead, you now know exactly which four knots you still have to practice. You get some new tips on how to tie them and you go home and practice some more.

“When you’ve gotten those last four down, you go back to the Scoutmaster, show him you know how to do all fifteen knots, and you get your merit badge. Then you move on to your next badge.

“I think the merit badge approach is a whole lot better way to think about tests than the traditional bell curve strategy. This way, taking a test becomes part of the learning process, a step along the way that tells you specifically what you still need to practice. You learn from your mistakes.

“Imagine for a minute that that’s how we do tests in this class. You’re not done with a topic until you’ve mastered it. Sounds good, right? For one thing, you will definitely learn more this way. Your grades will be better, maybe much better. The only way you can do badly on tests in this class is if you decide to quit working and not do enough work to be successful. That decision will be up to you.”

Jason is troubled about something; he looks around hesitantly before he speaks. “But if you need to go back and practice, doesn’t that mean the rest of the class is moving on without you?”

“No, it means you’ll be learning the new topic with everyone else and practicing the previous topic at the same time.”

He looks doubtful.

“Believe me, it can be done. You’ll have to manage your time well, but everyone in this room is fully capable of doing that.”

Ayesha, who has an amazing Afro, raises her hand. “What if you mess up a test and you don’t want to do the work to learn it? Will you be penalized?”

“The only penalties are that you didn’t learn from your mistakes and raise your grade while you could (there will be a time limit), and that you still haven’t learned something that may make it harder to learn the next topic. Physics is a great big structure, with a lot of pieces all interconnected. Leaving holes in the structure tends to hurt you later. It’s generally worthwhile to make sure you get it before moving on.

“But if you’re asking whether I will somehow force you to continue working and do retests, the answer is definitely no. On that list of my working assumptions that we talked about, there was one that says when people are forced to do what they don’t want to do, unwanted consequences happen. Well, I really believe that one. Personally, I don’t think it’s possible to force someone to learn anything. And even if I could, I would much rather you learn it because you want to, and that you enjoy the process. Using force takes the fun out of learning.”

Learning Takes Courage

Learning Takes Courage

Every year, there are a number of students who have poor mathematical skills. I find it helpful to identify them as early as possible; if we wait until they have already struggled or failed a test, the damage will be much harder to undo. Better to start working on those skills immediately. And that means there has to be an assessment of how proficient they are at those skills. The trick is to find out who needs help without scaring them at this delicate moment at the start of the year.

“To be successful in this class”, I begin, “there are certain mathematical tools that you will need. We use the English language to talk about how things work, but we also use the language of algebra, which turns out to be a powerful tool for describing the world very succinctly. We also use graphs and something called vectors and lots of diagrams. (By the way, one of the benefits of taking this class is that I’m going to teach you how to draw diagrams and sketches to express yourself.)

“Then there are all kinds of things you need to know, like the metric system and scientific notation for describing really big and really small things. My guess is that, if you haven’t used scientific notation or the metric system in a while, you’ve probably gotten rusty. So we’re going to spend the rest of today and all day tomorrow working on a station lab that I’ve set up in the back of the room. You’ll be able to practice some of these skills and see if they come back to you.”

Like most science teachers in this school, I have a large room; the front half of the room has a chalkboard and teacher’s desk along with collection of individual student desks arranged around the rug. The back half of the room features a dozen lab tables large enough to seat four or five students. Around these tables are wildly colorful old wooden chairs, painted and repainted by students. The chairs and tables all show a good deal of wear, carved up by generations of students. To my eye, they are a great antidote to the orderly look of the rest of the school.

I ask the students to come to the back of the room, where I have set up ten stations in order to allow them to review material they have seen many times in prior science classes. If they have already learned those skills, a quick review will probably be sufficient for them to retrieve what they know. If they haven’t learned them yet, they won’t learn them in this quick exercise. One by one, I show them each station and what they are going to do there. The tasks include measuring things with metric rulers, solving equations for an unknown, using scientific notation, and so on.

“Some of you are really good at these skills, like manipulating equations in Algebra for instance, and probably some of you won’t remember all of them. Rather than waiting until you are struggling in this class, let’s find out right away who needs to practice the necessary skills and do something about it -- get everyone up to speed as quickly as possible.

“A couple of days ago, I told you about the merit badge approach to taking tests. Well, I want all of you to have an algebra merit badge, and one for graphing and one for the metric system. After you’ve spent some time warming up and seeing how much you remember of these basic skills, you’re going to take a test on them. This won’t be for a grade; it will simply make sure that you and I know which merit badges you already have. And if you don’t have one of them, we’ll know right away what you need to start practicing.

“Here’s an important point about this class: once we know who needs to practice, only they will practice; if someone is good at a certain skill, practicing it would be busywork. I don’t want you to do busywork. You may be curious as to how we’re going to have a class where some people are doing a certain piece of homework and others aren’t. Believe me, we’re going to be talking about it a lot over the next few days and weeks.

“I need to say one more thing to you before you get to work: learning takes courage. Today, for instance, you may be working with people you don’t know yet. As you go from station to station, you will probably find you remember some of these skills, but not others. If you do know how, make sure you show the people you are working with how you did it.

“If you’re not sure how to do it, I want you to find the courage to ask questions about it. That’s the hard part; it’s scary to admit you don’t understand something, but it’s also the most powerful tool you have if you want to learn. So be brave. Ask questions.”

How to Take a Test

How to Take a Test

I appreciate the structure of the class so much, and I can really see that it has paid off. It’s so much better for me, personally, because I’ve always hated the whole system of working for grades. With this structure, I can actually learn, and not be scared to fail. —Anna L., student

They have finished the practice stations, and we’ve gone over them all to check their work. There was a lot of conversation while they were working, a lot of peer teaching going on informally. Every now and then a group would call me over because no one was confident about how to do that station. Even after a few days, the comfort level in talking to each other and in asking for help from me has improved markedly. We are starting to trust each other.

Now it’s time to attack the psychological baggage of test taking.

“We’re about to take the first test of the year. As I told you, there is no grade associated with this. Instead, this test will show you and me what skills you need to work on over the next few weeks, perhaps longer.

“A number of you probably have varying degrees of test anxiety. It is a very common problem, and it makes tests an ordeal. It also prevents you from showing how much you actually know. In this class, I’m going to do everything in my power to ease the pressure.”

Once again, there are lots of small reactions: smiles, nods, puzzled looks.

“First of all, over the next few weeks, I will hold workshops on test-taking skills for any of you who need them. There are tricks you can learn to overcome your fears and learn how to focus better.

“But here’s an even more important reason not to worry about tests; you can always recover from any test if you don’t do well. I’ll explain how this works later.

“Also, I will always allow much more time than the slowest person taking the test will need. I have no interest in finding out how well you can take tests under the pressure of time constraints. It doesn’t tell me what you know; it just tells me how well you perform under pressure, and that’s not something that I think is important.

“I promise you right now that I will never ask you a trick question. I want to know what you have learned, and I will ask straightforward questions to find out. So you don’t have to try to second-guess what I’m after.

“Also, while you are taking tests in here, I will remind you periodically to look up, breathe, relax, get your head out of the test. All too often, people taking tests go into a kind of trance, and they can’t think clearly or creatively. Just taking a few deep breaths clears the head. It turns out your brain needs oxygen to think clearly.

“Finally, when you are least expecting it, I will tell a truly bad joke, a groaner. If that doesn’t break the spell, I don’t know what will.”

Lots of smiles.; they obviously like the idea of lightening the mood oftest taking.

I hand out the tests, remind them that it’s not for a grade, and they begin.

Cultivating Grit

Cultivating Grit

Fall down seven times, stand up eight. —Japanese proverb

One of the unintended casualties of traditional test-taking is the important attribute of tenacity. Imagine you are a student who does badly on tests in, say, algebra. When you get a test back, there may be a review of the correct answers, you put the test away and move on to the next unit with the rest of the class. Because there is no mechanism for learning from your mistakes, you are prevented from responding to the problem, whatever its cause. You are, in effect, being trained to acquiesce in the face of failure.

This experience is, of course, demoralizing and even humiliating, especially if it happens over and over. Equally bad, an opportunity to learn to have grit in the face of adversity is being squandered; students are trained not to have tenacity, to stand back up and figure out how to recover. Multiply this experience by millions every day in schools everywhere, and you can see how this one structural problem can have widespread social consequences.

The ability to see mistakes and failure as feedback is an essential attribute of an effective learner. So is having grit in the face of negative feedback.

Grit is an essential attribute of self-directed learners. Without it, the motivation to persevere when the going gets tough dwindles, and the learning process is stymied. Test remediation techniques can directly train students to have tenacity in the face of failure. Students can learn to push through self-imposed ceilings on the their academic success. And in so doing, they also practice a life skill that is important in every future endeavor.

Learning From Mistakes

Learning From Mistakes

I am about to hand their first test of the year back to them. I want to convince them that there is another way to think about the results of this test.

“As always, some people did better on this test than others. The question I want you to think about when you get back your test is what are you going to do with it? Let’s say you find that you did much worse than you thought you had - it happens some times. Under normal circumstances, what would you do with that?”

Layla, who in fact did pretty well on this test, says, “I would probably take a quick look at it and stick it in my pack. I might show it to Annie and do a little private groaning, but then I definitely wouldn’t want other people to see it.”

“And what about later - say when you get home. Would you look at it again? Or share it with anyone else?”

“I probably would look at it, just to see what I got wrong and if it seemed fair. As for sharing, I might email a friend or two and moan about it.”

“Anyone else have any thoughts on what you would do?”

“Mine would go straight in my pack. I wouldn’t even look at it.” This is Suzanne.

“And then?”

“Probably into the pile at the bottom of my locker.” There is some laughter. Apparently, Suzanne is known among her friends as having a locker that is seriously out of control.

“Okay. Here’s the thing. What you do with a test when you get it back is actually important. If you did badly, you might feel ashamed, or sad, or angry at yourself or me or school in general. Even though these are pretty normal responses, none of these emotions are useful. In fact, they are really counterproductive.

“When you crumple up this test and throw it in the bottom of your locker, you are ensuring that you cannot possibly learn anything more about this topic. The process is done. You are shutting it down and moving on to the next topic.

“But this test is telling every one of you something really important. It is shining a light on the boundary between what you do know and what you don’t. And that boundary is exactly where all learning takes place.

“Take a look at today’s quote: I point to the the white board, which reads: “Failure is an opportunity.” Lao Tzu“Anybody have any thoughts about what that means?”

“If you mess up, you can recover,” Jess says.

“You need to look on the bright side of things,” Cassandra adds.

“Don’t be afraid of making mistakes,” Carl says.

“Do you remember the story of the Boy Scouts and their merit badges? It’s time to start thinking of tests that way. If we’re thinking about tests that way, what should you really do to make tests useful? How could you use them to learn from your mistakes?”

“Look at the problems we got wrong, right?” Suzanne asks.

“Yes. But I’d like you to start thinking of those problems in a new way: it’s not so much that you got them wrong, it’s that you don’t know how to do them correctly yet. That leaves you open to doing more work, figuring it out, and showing me that you have learned from your mistakes.

“Consider for a moment the idea that everyone in this room is fully capable of understanding all the content of this class. I can tell you honestly that I believe that. And if that’s true, the reason why not everyone aced this test is because some of you haven’t finished the process of learning it yet. It’s really that simple.

“We know everyone learns in a different way and at a different pace. If we are truly dedicated as a class to the goal of everyone learning physics successfully, why would we punish thos of us who are taking longer to master the material? We wouldn’t. Only you, every one of you, should have the power to decide you have learned as much as you are going to. That’s why the process I’m about to show you is voluntary. It is your choice.

“So, let’s take a look at how you can learn from your mistakes. Over the years, I’ve developed a process called a test resubmittal,” I hold up a sheet of paper, “and here’s how it works. If you got a question wrong, you need to figure out why you got it wrong - exactly what were you thinking? Obviously, you also need to know not only what the correct answer is, but why it’s the correct answer.

“Your task is to look carefully at every question you got wrong on the test and show clearly and convincingly that you now understand it. Doing this work will improve your grade, especially if you did badly. More importantly, this process gives you a way to complete your understanding of the material before you move on to the next topic.

“But you can’t do this process very well by yourself, and you can’t all depend on me to explain and help you learn the material - there’s not enough of me to go around. It is much, much better to work with other people and talk to them about how they did the work, ask them about how they got it right. This is a principle function of the study groups, and it is where a large part of your learning will take place.

“And that means you are going to have to overcome your shame or anger or sadness, and find enough courage to put your test on the table where others can see it. You need to be able to say, “I need help with these three problems - how did you do them.” That is going to require a lot of trust. It will get much easier once we’ve chosen permanent study groups and you’ve gotten to know the people in your study group members much better. In the meantime, just while you are going over this test, I’ll let you form your own groups so that you can work with people you already know. Let’s say a maximum of five in each group, and I’ll work out the details with anyone who for any reason doesn’t find a group to be in right away.

“Usually, there is at least one person in each group that got the problem that you messed up. If no one in your group got it, call me over and I’ll work with you.”

I hand out the tests, give them a minute to look at them, and say, “Okay, once you’ve made up your groups, introduce yourselves if there’s anyone in the group that you don’t know. Then go over every question that anyone in your group missed. If you got any of them wrong, I want you to get out your journal, title a new entry “Test Corrections”, and put the correct solution in there. It’s okay to copy it over from someone who got it right, as long as you can see how it’s done at a later time. If you are going to do a retest later on, this is a required step in the process. I’ll go over the other steps later. Remember, if you take this process seriously, you will not only improve your grade, but more importantly, you will learn more.”

True Negatives, False Postivies

True Negatives, False Postivies

Tests measure only how many test questions a student can answer correctly at that moment. How that knowledge got there, how long it will stay there, and how meaningful it is to the student are not being measured, even though most teachers would agree that such matters are truly important. Since there is no reliable way to know what a test score means, it is important to know what it probably means.

When a student fails a test, there is a strong possibility that the student didn’t understand the material. Let’s call that a true negative. But it is also possible that other factors, like test anxiety or even personal issues can create false negatives: the student knows the material, but the test doesn’t show it. When I was in graduate school, I had knee surgery. Several days later I flat-out failed a test in my heat transfer course (yes, there are whole courses about heat transfer), a course in which I had previously aced every test and would for the rest of the course. To this day, I have no idea how that happened, but that is a classic false negative.

As for people who do well on tests, a true positive means a good test score representing true learning. A false positive would mean a high score, but little or no genuine learning. From the self-reporting of my students, false positives (or partial false positives, where a student aces a test but has only learned some of the material) are commonplace, perhaps even the norm. I recognize this is not a valid sociological study, but studies of long term retention rates are, and they confirm the broad level of misleading test scores. It is simply not credible that the students who have exemplary test scores in class after class are forgetting what they “learned” in a matter of weeks or months. That’s not learning, but it sure looks like it - a classic symptom of doing school.

In a sense, trusting that high test scores mean learning has taken place is like asking a class “Are there any questions?”, and assuming that when no one has any questions it means everyone understands the material. They are both false positives.

When a teacher realizes he cannot trust or control the meaning of test scores, it is a humbling experience. No one can ever make good test scores into true positives. All a teacher can do, all he should do, is shape the classroom culture into one where the student prefers learning over cramming and forgetting, prefers honesty over the dishonesty of doing school.

A realistic teacher will recognize that only the student can truly know whether he has been learning or cramming, and that that is as it should be. It is exactly when a teacher uses forceful, intrusive tactics (pop quizzes spring to mind) that he becomes part of the problem and increases the ammount of doing school occurring in his classroom. Since his goal is to reduct the act of doing school as much as possible, such tactics should be used sparingly, if at all.

What Are Tests For?

What Are Tests For?

If we accept the premise that tests cannot measure learning, what would a legitimate use be? It turns out that how we understand the purpose of testing is a window into the more fundamental question of what we think schools are for.

The lure of the false positive for a student is that it seems quicker to cram for a test and get a high score than to actually learn the material. If a student is doing school, a false positive counts as much as a true one; the goal of school for him is to get good grades, and a test score isequally valid whether it represents genuine learning or not. Unfortunately, this point of view is truly pervasive.

What a teacher wants is for students to have true positives, that is, high test scores that occur because of solid understanding of the material. Unfortunately, in my experience many teachers aren’t aware of the existence of false positives, or can’t or won’t distinguish between true and false positives. Their response when students do badly on a test is to try to help them raise those scores. This can happen while still remaining blind to the difference between true and false scores.

The question we should be asking is not how to raise low test scores, but how to make the learning process so effective that high test scores actually mean something. Even more importantly, we need to see whether test-taking can become a meaningful, even an essential part of the learning process.

As shown at the start of this chapter, low test score can be re-imagined as important feedback on what a student still needs to learn. In educational jargon, these are called formative tests. That is a very different purpose than when tests are considered results that occur at the end of a unit. These are called summative tests, and they serve little purpose in the learning process. They do serve another purpose which, as we shall see, leads to a number of unspoken consequences that have serious negative effects on students and how they learn.

The Hidden Purposes of Testing

The Hidden Purposes of Testing

After having gone through a few test cycles, it’s time to continue the conversation about the meaning and purpose of tests.

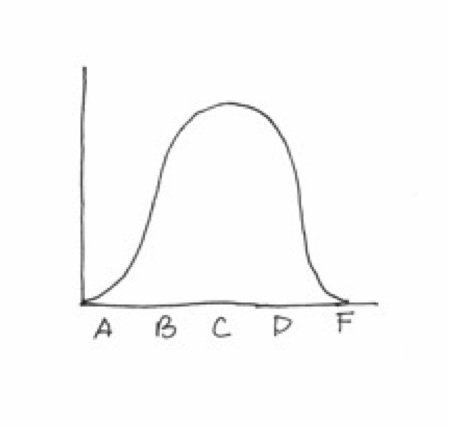

“In most classes, everyone takes a test at the same time and the grades form what is called a bell curve. It’s a classical distribution of grades from A to F. Some people believe that good tests should sort people into this kind of distribution.”

I draw a bell curve on the board.

“Some students get As, a lot get middling grades, and a few fail. When the class gets the test back, maybe you go over it, maybe you don’t. Then you promptly move on to the next unit. A couple of weeks later, at the end of that unit, you take another test and the grades for the class form another bell curve, probably a lot like the last one. The same people who got As on the last test will probably get an A again. Same thing for the people who failed or did badly.

“Does this sound familiar?” Again , there is a chorus of agreement. The only debate is about how many of their classes do a meaningful review of tests when they get them back. It’s clear that different teachers have widely diverse ways of handling the issue, from returning tests without comment to reviewing every question on the test. Above all, there is a sense that the whole process of taking tests and getting them back is generally frustrating and not particularly helpful.

“Since our goal is to have everyone in this room be successful at learning, we need to undo the bell curve. The test resubmittals can help us do that. The truth is, the purpose of a lot of the structures we have in this class is to do that. We want to get out of the sorting business.”

“I get that sorting is not a good thing, but it’s also true that some people learn more than others,” Steve says. “Are you saying everyone should get the same grade? If we get away from the bell curve, is that fair for people who are working harder?” He doesn’t say it, but it’s clear that he’s talking about himself. He has never had less than an ‘A’ on a test, and he consistently has the highest test scores in the class. This argument often comes up because students who do well feel threatened - they are concerned that they will not be acknowledged as excellent students.

“That’s a great question, Steve. It gets to the heart of a problem that I’ve struggled with as a teacher for many years. I believe in my heart that if we as a community hold the goal of everyone successfully learning the learning goals of each contract, we can actually achieve that. I also know that some of you have a better intuitive grasp of physics, or have a stronger math background or just plain work harder. I agree that it wouldn’t be fair not to acknowledge that some people will learn more deeply than others. And grades are the only available way we have to do that.

“So we have dilemma. If you remember the story of the merit badges I told you the first week, I said that a person learning how to tie knots would get a badge if he could tie fifteen knots correctly. Now, if we go with the bell curve process, we’d all study knot tying for the same amount of time, we’d take a test, and some people would tie twenty-two knots and some fifteen, but some would only tie, say, nine correctly. We’ve got our bell curve. We know who the great knot tiers are, the pretty good knot tiers, and the failures. And then we would move on together to the next topic.

“What test resubmittals allow the people who only got nine knots right to do is keep practicing until they get to fifteen. Now I would say that a fair grade would acknowledge that there is a range of depth of learning, but it doesn’t require anyone to fail. If we’ve done it right, everyone in the room is successful at having learned the essential ideas and skills. And at the same time, there will be grades, and they will be based on the depth of how well you learned.

“Our goal is mastery for all. We do everything in our power to help each other reach that goal. When some people do better than what’s required, by doing Above and Beyond items on the contract for instance, or really nailing the tests, we can acknowledge that with a better grade. The job is for every person to challenge him or herself to reach a personal best and trust that the grade will follow. If we pull that off, we can still have grades without contradicting our goal.

The Sorting Machine

The Sorting Machine

Tests are often the principle academic sorting mechanism in a classroom. This is not some afterthought, but an intentional function of testing. I remember one particular science department meeting in which the design of good multiple choice questions was being discussed. In particular, we were exploring how to construct good “distractors”, the answers that are incorrect that will lure students who don’t understand the material covered by the question. If a distractor is too far afield from the correct answer, it is too obviously incorrect and won’t get chosen very often. On the other hand, the distinction between the correct answer and the distractors must be clear so that it will separate students who really understand the material from those who don’t.

In other meetings, we discussed how a well designed test should also have questions with a range of difficulty. There should be some easy ones, so that everyone would have at least that much success, some in the middle range, and some really difficult problems that only a few strong students would be able to get. The idea was to discriminate between students who had learned the material deeply and those whose understanding was superficial.

All of this makes sense; writing good tests is an art form that takes years to get good at, and discussions like these clarify the skill involved. Unfortunately, this kind of thinking can lead to using the test to sort students into a bell curve distribution, which is often the intent of the teacher. The question that is often not addressed is what happens once you have sorted them.

By definition, our use of grades requires some significant number of students to be unsuccessful academically. We profess that we want everyone to be successful, but what would really happen if everyone got “A’s”? Wouldn’t we have to “dumb down” the curriculum to accomplish this? How would colleges be able to select the “right” students? We can’t imagine not actually sorting students by academic success, so when we say we want all students to succeed, we probably mean having a lot fewer D’s and F’s. A bell curve makes it difficult to imagine a learning environment where everyone is truly successful.

Grades condemn teachers and students alike into becoming cogs in a sorting machine.

The question arises, what would happen if everyone in a classroom consistently aced tests? Would the teacher be considered too lenient? Must it imply that he is dumbing down the curriculum? And if everyone did this, how would colleges decide who could be accepted? In fact, the current structure of our educational system seems to require a bell curve.

The standards movement is a recent approach to school reform that was designed to determine what the baseline of curriculum that every student needs to master. In my high school, a great deal of time and effort went into the definition of those standards, and even more into the creation of “common assessments” in order to identify whether every student had mastered the same level of competency.

In a number of meetings, teachers asked “but what happens when students don’t meet those standards?”, and I have to say that in all those meetings, I never heard a satisfactory answer. The idea of grades being used as a sorting mechanism is deeply embedded in the structure of the educational system. The standards movement ran into the brick wall of the bell curve. In that battle, the structural imperative to sort students wins.

The Bell Curve on Steroids

The Bell Curve on Steroids

In the fall of 1972, I moved to Germany to take a teaching position in a Gymnasium. I was brand new to the German school system, and an idealistic young teacher. In an Algebra class, I worked hard with my students and on their first test everyone in the class did well. I was thrilled - they had learned a great deal and showed what they had accomplished.

The next day, I was summoned to the principal’s office. He told me in no uncertain terms that I could not do what I had just done - my tests had to separate students with excellent scores from others with low scores. I needed to create a bell curve.

He went on, and explained that in the German system, which has a two track education system, not every Gymnasium student could go to University when they graduated; there simply weren’t enough places. So part of the function of the Gymnasium was to identify the strongest students and eliminate the weakest. There was even a guide book to identify under exactly what conditions a student would drop down from the Gymnasium, and the promise of a white collar job, to the Volkschule and, most likely, a career in the trades.

At least in Germany they were overt about the structural need to sort students by academic strength. But in the American public school system, it is a fundamental belief that everyone should finish high school. The way out of this bind is social promotion, moving a student up because his class is moving up. This often allows students to graduate who have been poorly served by schools and are seriously lacking in skills and training.

Isolating the Difficulty

Isolating the Difficulty

“I’m about to hand back your first skills test. One of the reasons why I give you two tests, one about the concepts, the ideas of physics, and the other about the problem-solving skills you are learning, is that how you recover from not doing well on each is going to be different. You remember that for the concepts test you can write a resubmittal, essentially writing about what you didn’t understand, and showing that you have now learned it.

“But for skills tests, I still find that the only way for you to show that you know how to do it is by actually solving problems on a test. So if you didn’t do well on this test, for instance, here’s what you will do.

“First, you’ll get together with your study group and go over every problem you got wrong. You want to write the correct solution in your journals under the title “Test Corrections”. Then, I’ll give you another problem set with the same kind of problems you had on this test, and you will practice them at home, making sure you can do them independently. You can get help from me or anyone in this room. Finally, you’ll meet with me and we’ll go over a few problems together so that I know you’ve been practicing. Then I will know that you’re ready to take the retest. That will be a test with similar problems to the one I am handing back today. If you’ve done the process well, you should be ready, and should be able to do well on the retest.

As always, I wander from table to table, overhearing the conversations, guiding the discussions judiciously, answering questions that the whole table has. As I listen, I hear the beginnings of what I know will become one of the most effective learning techniques that I know. When a student asks “how did you get number 3?”, the student who got it right can explain it in a more personal, sociable manner than if we were all sitting in the front of the room, and I was throwing it on the overhead. With time, I will help them learn how to dive more deeply, with more subtlety in figuring out the specific crux of why they got it wrong. I call it “isolating the difficulty”, and whether they are going over homework or reviewing a test, it is an essential skill in learning effectively.

Defining What Matters

Defining What Matters

In the process of planning backwards to design a unit of study, the first step a teacher might do is to decide on the learning goals; what should a student know and be able to do at the end of the unit? And the next step is generally to design assessments so that both the teacher and the student will know whether mastery has been achieved.

It seems clear, then, that tests should directly reflect the learning goals, even help clarify them. Unfortunately, tests often inadvertently cause tests to assess totally unrelated skills, often with serious unintended consequences.

One of the most common is intentionally giving students not enough time to finish the test. The justification, if there is one, is that time constraints can discriminate between students who really know the material from students who take too long and don’t finish the test on time. Unfortunately, this cruel practice also generates high levels of stress and anxiety in many students. If the skill of showing what you have learned and doing under intense pressure is something we want students to master, we should let them practice this skill and train them how to do it well. I personally find it hard to see how this could be considered a useful skill in life. And if it isn’t, the damage that is done to students is needless and, in my mind at least, inexcusable.

In Illinois, the ACT test is part of the standardized tests mandated by No Child Left Behind. I have taken the Science Reasoning portion of the test, and I have done quite badly because I can’t seem to help trying answer the questions based on actually understanding the readings that the questions are based on. There is, by design, nowhere near enough time to do that.

Like every teacher in my school, I would spend one whole week training my students how to raise their ACT scores. This training consisted largely of teaching them techniques that would shave seconds off of answering each question - teaching them how to skim the reading passage after reading the question to find the answers as quickly as possible. The pointlessness of this activity, combined with how little most of the questions have to do with any content or skill that we actually teach in high school, are a major indictment of the whole process. I cannot imagine designing a process that would relate less to what we do and what we hope to accomplish with our students in school.

Zenani's Story

Zenani's Story

"By you acknowledging my problem of test anxiety, I was able to work with you to break down step by step what I need to do to become better and just showing what I know through the test. It’s hard to believe that it’s now junior year and someone is just acknowledging my test problem—even when I tell a teacher they seem to simply ‘not care’ and don’t want to spend time working with me." —Anna L., student

If there were an award for sweetness and light, Zenani would win it, hands down. I have rarely met a gentler person, or one with a more positive posture towards life.

We are meeting before school because she wants to talk about her test grades, which have been consistently low, rarely above failing.

“I don’t know why it happens,” she says, “but I freeze up whenever I take a test. I just stare at the paper - I can’t think straight.”

“Zenani, we need to figure out specifically what’s happening when you take a test so we can come up with a plan to make it easier for you. Let me ask you, do you have this trouble with tests in all of your classes?”

“Yes.”

“And has this been true for a long time, or is it getting worse?

“I remember clearly being in third grade doing the ISAT test, and being terrified. And what was worse was we had to announce how many right we got on the practice tests in front of the whole class. So while other people were calling out 28 or 30 out of 36, I had to call out 18. It was humiliating. But the point is, I was already choking on a test.”

“I’m really sorry to hear about that - it’s unfortunate when teachers think you will do better if you have to work not to be humiliated.”

“Yeah, and my seventh grade teacher did the same thing.”

“Well that’s too bad. But do you have a sense about how much of your anxiety has to do with time constraints? Lots of people with test anxieties freak out when they are afraid they won’t have enough time to finish.”

“Timed tests are what sets it off, no question.”

“Now, in our class, I design the tests so that everyone has plenty of time. That doesn’t seem to be helping you that much, though.”

“No, even knowing there’s lots of time - I do it to myself. When I’m panicking, it’s like I get stuck and time goes by and I’m just not thinking much.”

“Let me ask you this then; do you believe you can do the required level of difficulty successfully when you are doing homework?”

“Definitely. I get to the point where I don’t need helpful hints, and I’m getting the problems right by myself.”

“And when you have the same level of problems on the test, you can’t do them, is that right?”

“Yes. It makes me crazy, knowing that I know how to do this, and blanking on how.”

“Okay, this is a place to start then. We’ll begin by doing homework together before school, if you can do that - “

“ - I can - “

“ - and after I see that you can do them, I’ll give you the same kind of problem, but with a time limit. It’s still not a test, and I’ll be there to talk to, so we’ll see if you can do that. Meanwhile, I’ll have a much better sense of how successful you really are, which will allow us to talk about your test grade much more accurately when we do grade conferences at the end of the quarter.

“If we need to, you can do the next few tests in this room during your free periods, and you can talk me through what you are thinking. I will be here to help you stay calmer, if you can. And don’t forget, no matter what happens, you will always have the option to do a resubmittal or a retest, if you need to.”

Over time, Zenani makes some progress in controlling her fears. The classroom environment helps a lot, and the process of graduating from doing homework successfully to doing tests fairly successfully helps. She also discovers that the sound of water gurgling in the bubbler I have on the side counter is soothing, so from that point on, she does her practicing and takes her tests sitting right next to the bubbler. I believe that when she realizes she has some control over her situation, it helps subdue the panic.

But if we set aside the lower grades and the academic damage that this test anxiety has done to Zenani, there is the humiliation, the loss of self-confidence and self-worth that is truly insidious. And for every Zenani, who has the wherewithal to articulate what’s happening, there are a hundred others who silently internalize the damage.

The Opposite of Cramming

The Opposite of Cramming

"I never even need to look at the book while studying for a test. If I have paid attention in class every day and if I take good notes, then all I need to do before a test is study my notes so all those ideas are fresh in my brain." —Liz L., student

When students are learning effectively, cramming for tests becomes unnecessary. By the time the test happens, they already know the material. Reviewing for the test means double-checking for possible weak areas, polishing the learning one more time, and getting an overview of what has been learned. The test itself becomes a check-up.

How students prepare for tests is an excellent indicator of how well the culture of learning is functioning. When the process is working well, learning is continuous and the test is just a snapshot of the state of that process.

Similarly, preparing for a semester exam is an opportunity to give the student an overview on what he has learned and let him identify areas that need more work. However, if real learning has been taking place, preparing for an exam should not require extensive practice.

If we imagine a spectrum stretching from memorizing and regurgitating on tests on the one hand, and true, deep learning on the other, preparing for an exam is an excellent opportunity for students to see where they are on that scale.