If a student is trying to master a specific skill, remediation will in general require more practice of that skill. If the goal is, say, learning how to factoring an algebraic equation, there is no substitute for factoring more algebraic equations. This practice will generally be followed by a retest to assess whether the student has, in fact, learned from his mistakes.

A central feature in designing remediation for skills-based content is a breakdown of a complex skill into its component subskills. As described in “Unit Contracts”, the learning process for such complex skills should be scaffolded around the introduction of a set of discrete subskills. In this way, the student can build towards complexity. He can be given feedback on each subskill in order to practice problem areas and build on his successes.

Similarly, the structure of both the test and its remediation should mirror that scaffolding and make the subskills visible. For instance, if a complex problem on the test requires of a number of subskills, each step can be considered an independent part of the test problem. Here is an example of the test question and answer showing the physics problem-solving scenario described above. Notice that the instructions for the problems indicate which steps are required, each of the steps is shown in sequence in the answer, and each is graded (with a “c”) separately.

Requiring the student to show each subskill explicitly in any complex problem and valuing each step as a part of the grade encourages the student to show all of his work. It also reinforces the student’s mastery of the problem-solving process and teaches him to trust that process when he gets stuck.

The test itself can thus serve the purpose of isolating the difficulty — helping the student to identify specific problem areas. Getting any step wrong tells the student that he must continue working on that subskill. Remediation can then allow the student to practice intensively, just as someone learning the piano will play a problematic musical phrase over and over until it is mastered.

If learning contracts are being used, a remediation contract can give a student the choice to practice only the specific subskills that he needs. An example of a remediation contract is described in detail in “Learning Contracts”.

The discovery phase of remediation should ideally be concluded with a checkup so that the student gets feedback that he has indeed mastered the skill before retesting.

Finally, remediation of skills must end with another assessment. The most practical means of assessing mastery is a retest, a second version of the original test, with similar skills-based questions. For students who struggle with test anxiety, this can be accomplished by having the student work through a problem similar to one on the test, explaining the process step by step to you.

The remediation of writing skills.

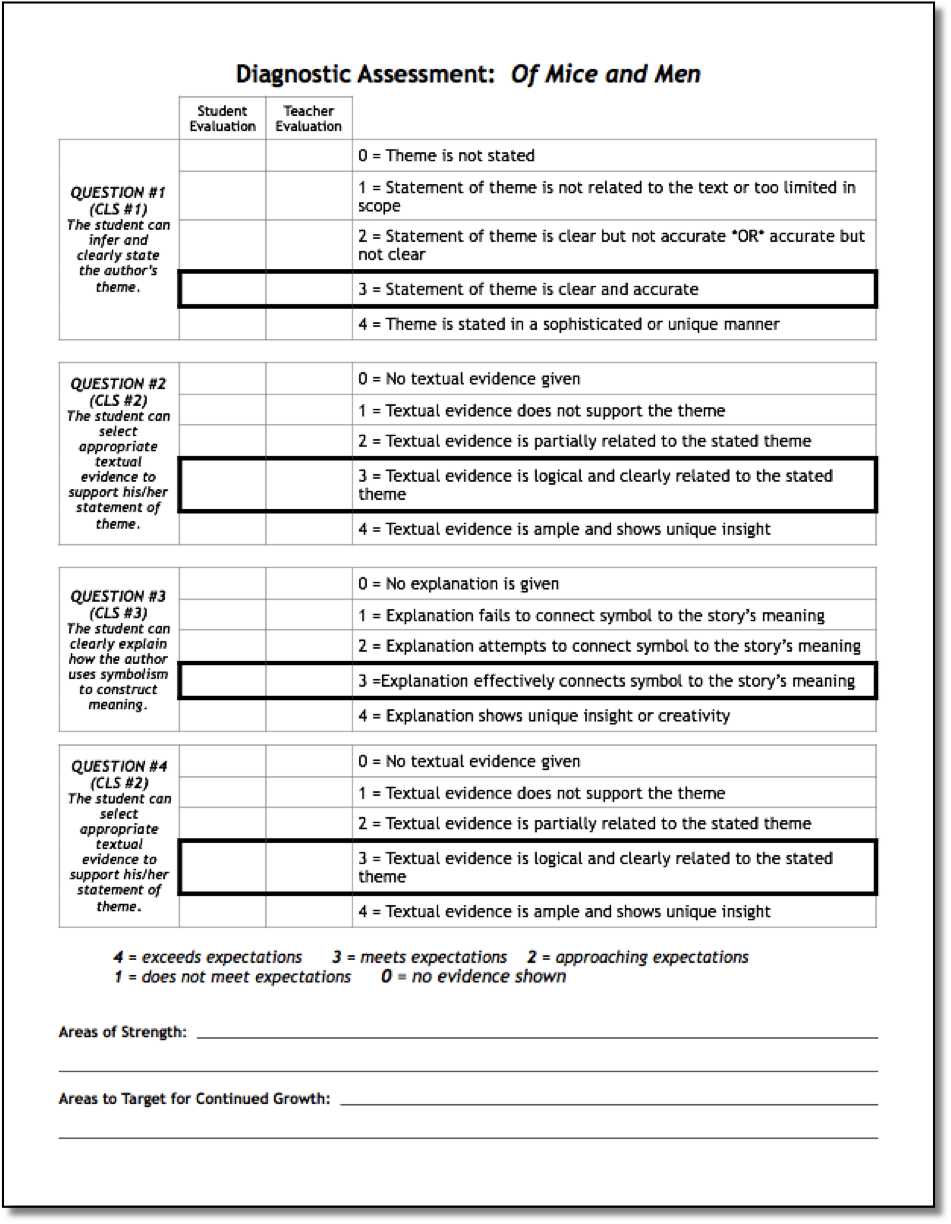

When writing skills are being assessed, the strategies described above may not be practical in identifying areas that a student needs to continue working on. In that case, a structure must be created that allows for a direct assessment of specific aspects of a student’s writing. An example is shown below. Once such an assessment exists, a remediation process can be constructed that allows a student to work specifically on the areas that he is struggling with.