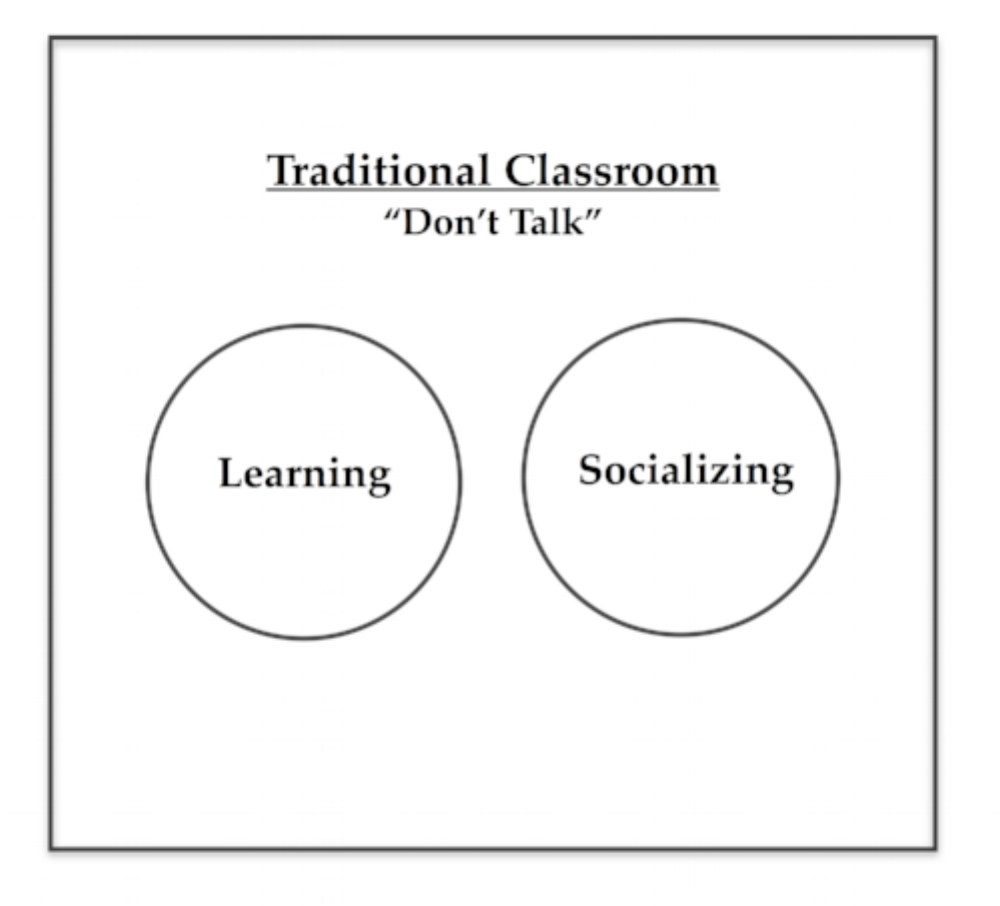

In many traditional classrooms, socializing is seen as a distraction from learning. This diagram expresses an all-too-common response to the natural desire of students to talk to each other.

The rigid separation of these two domains is unnatural and deeply counterproductive. Maintaining it requires endless vigilance on the part of the teacher and lends itself to unnecessary power struggles. These are teenagers, after all, and socializing is, for most of them, a very high priority. Fighting it can often feel like trying to hold back the tide. Fortunately, relinquishing that struggle will actually improve learning.

Students teaching and learning from each other, questioning and arguing and patiently explaining new ideas to each other, is a central aspect of a community of learners. That means students have to talk to each other. Recognizing the centrality of conversation learning requires a different way of thinking about socializing. For students to understand that teaching and learning from each other is an essential tool, they must be trained to be able to socialize and learn at the same time. In other words, they must learn the art of appropriate socializing, as seen in this diagram.

In this diagram, there is significant overlap between the learning and socializing. There will still be individual learning, of course, as indicated by the area to the left of the overlap. This can include listening to an introductory lecture, doing homework, taking a test, or any other solitary activity.

There will also be socializing that is unrelated to learning, as indicated by the area to the right of the overlap. While this may at first seem to be a waste of time and a distraction, it is, within limits, essential in developing the social glue necessary to develop trust and a sense of belonging within the group. Having students learn to self-limit this aspect of group work to a reasonable amount is part of the skill of appropriate socializing.

How much is enough? In general, I have found a goal of 80% to 90% on-task behavior, regardless of the activity, is reasonable. I believe this is a realistic acknowledgment of human nature, but of course you will have to decide for yourself, given your particular students and your own preferences. Before you do, though, I would encourage you to think about department meetings or whole-school presentations you have attended. Was every person in the room 100% attentive the entire time? If not, why should we then expect it of our students, who are, after all, teenagers, and hard-wired to socialize?

This is an excerpt from "Study Groups: The Heart of Conversational Learning"